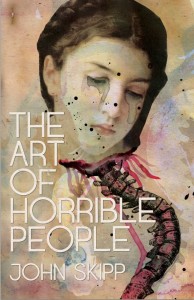

John Skipp

Lazy Fascist Press

August 15, 2015

Reviewed by Tim Potter

John Skipp’s new book, The Art of Horrible People, is something special. Not only is it a great addition to his already prodigious body of work, but it’s all his, every word. For a man whose best known books are collaborative efforts, it’s a rare treat and a glimpse into John Skipp’s head and heart. The collection ranges from short, playful fiction to an extremely personal farewell to a good friend in one of two non-fiction entries. As Bird Box author Josh Malerman points out in his excellent introduction, there is more to the stories than just horror, something unique to the author. Whenever John Skipp puts pen to paper there is always an underlying theme of exuberance, a lust for life that makes his horrors all the more powerful.

The first story in the collection is possible its finest. “Art is the Devil” opens at the Los Angeles Hyaena on Charlie Sheen Night. Everything there, art in all of its forms, are inspired by Charlie Sheen.

“Hyaena had set the bar high, in the lowest way possible. And that was a beautiful thing.”

It’s a story about art, exploitation and what is really transgressive. The main characters meet a mysterious man, Max Apocalypso, who invites them to leave Charlie Sheen Night and to come to his show, which he insists is truly transgressive. The exhibit turns out to be something akin to a Satanic funhouse, filled with gore and the gruesome and very real violence. The story calls back to the 1980s Satanic Panic and does a great job of turning many of the tropes related to it on their heads. And in the end, when the devil appears in the flesh, the story comes to a perfect circular ending.

“Depresso the Clown” is told from the point of view of a man held prisoner in a basement. As the story develops the reader finds out how the clown (the narrator and prisoner) came to be in that basement. Why is his clown nose being sewn permanently to his nose? Why is his clown makeup being tattooed on his face? Clown torture is rarely this much fun.

The zombie tale “Rose Goes Shopping” is short but a bit deeper than the average zombie story, exploring the parallels between zombies and the way some people feel when medicated with psychopharmaceuticals. Also, the idea comes up that there may be times when the human actually finds themselves rooting for the zombies. “Worm Central Tonite!” is a fun exploration of a very unique POV. “In the Waiting Room, Trading Death Stories” is an ambiguous but compelling tale of impending death.

“Zygote Notes on the Imminent Birth of a Feature Film as Yet Unformed” is another exploration of art and its creation. The story of a filmmaker on a relatively normal trip to an unfamiliar town results in the formation of an idea for a film. The process of bringing a film to life is likened to the conception, birth and raising of a child.

Los Angeles is a central setting and theme throughout the collection. The author takes on the movie business with “Skipp’s Hollywood Alphabet Soup of Horror.” Every letter of the alphabet represents an important part of the movie business and is illustrated with absurd, overblown, melodramatic and inarguably hilarious vignettes. The wordplay and satire are the focus here as a traditional narrative is abandoned in favor of a free verse structure.

“Food Fight” is a bizarre and, at times, hallucinatory trip through a mental institution in the midst of a disaster. The point of view rotates quickly through a cast of characters populated by doctors, orderlies and all kinds of crazy. Taken together these independent narratives converge as the facility falls into chaos during a desert sandstorm. While “Food Fight” is entertaining it does feel a bit unfocused at times and it’s the only story that doesn’t fall into the themes of art and LA.

The highlight of the collection comes at the end with two unexpected and deeply personal pieces of nonfiction. “Appendix A: Roughly One Thousand Reasons to Love the Fuck Out of Art (Even if You Hate the Ones Who Made it)” presents an argument that unless one can separate the art from the person who created it, they will, inevitably, be missing out on great art. Skipp contends, convincingly, that art should be enjoyed because of the art itself, not because of the person who created it. It’s an approach that could well be applied to the ongoing discussion in horror and fantasy circles about H. P. Lovecraft and his racist personal views. The author also gives the reader a list of over one thousand artists whose work has been important to him, any number of whom are horrible people.

The Art of Horrible People ends with a simple, emotional response to the death of the author’s dog, Scoob. “Appendix B: Scoob’s Last Will and Testament” conveys the sadness of the loss of one’s pet while focusing on the joy and beauty it brought to the world when in could. It’s a brief but emotionally complex work that brings the collection to a highly satisfying and emotionally honest conclusion.

- Midian Unmade – Book Review - September 30, 2015

- Wolf Land – Book Review - September 16, 2015

- Convalescence – Book Review - September 7, 2015

- Rage Master – Book Review - September 3, 2015

- The Art of Horrible People – Book Review - August 28, 2015

- Greasepaint – Book Review - August 26, 2015

- Bonesy – Book Review - August 17, 2015

- Dark Screams: Volume Four – Book Review - August 13, 2015

- Trust No One – Book Review - August 10, 2015

- The Monstruous – Book Review - August 3, 2015