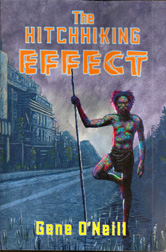

Gene O’Neill

Dark Renaissance Books

2015

Reviewed by Michael R. Collings

It is rare when a collection of stories and novellas spanning some thirty years leaves me with a single, overwhelming emotional impression. In the case of Gene O’Neill’s The Hitchhiking Effect, there is an additional sense of the unusual in that his compilation of ten stories—most dealing with the physically, mentally, and emotionally debilitating effects of war on those most closely connected with it, whether serving or supporting—contains its share of realistically portrayed grief and loss, of violence and bloodshed, of death and disruption, yet when I finished the final story, “Firebug,” what I felt was a highly paradoxical sense of gentleness and peace.

In “The Burden of Indigo,” for example, the earliest of the stories, O’Neill introduces readers to a world in which criminals are punished by being stained, a specific color representing a specific crime. The main character is known simply as “the indigo man” and is a deep, rich purple-blue from head to foot, including his hair and clothing. Such Colored People are ostracized from the domed communities where humanity now lives and are doomed to wander the empty stretches between. The story deals with his increasing belief that his indigo is fading—that he is perhaps gaining some kind of exoneration, a cure, for his unnamed (but implied) crime of two decades before. Yet even as he feels a nascent hope, he must deal with the fears and prejudices of normals he encounters, until his final meeting with a strange, almost mystical figure, who in the most unusual way, alleviates his suffering.

In the final novelette, “Firebug” (first published here), a neophyte arson investigator is assigned to a series of fires in abandoned warehouses, the most recent of which killed a homeless person. As clues accumulate, he is forced to include among his prime suspects his own father. While that story progresses, however, readers enter the mind of the firebug through journal entries, following an all-too-familiar progression from abused childhood, to traumatic loss of parents, to infatuation with violence and destruction…in this case, a developing pyromania. Oh, and along the way, O’Neill reveals that the pyromaniac is not technically the Firebug—there is an actual (?) fire-bug inside the flame of a cigarette lighter that, when released, causes the conflagrations. The story ends, as it should, in the discovery of the perpetrator and the resolution of unsolved cases, but again, as with “The Burden of Indigo,” there is a powerful sense of rightness, of peacefulness and gentleness and ultimate reconciliation.

I’ve chosen to write at length about the first and the last, but other of the stories could have demonstrated my point. “Graffiti Sonata” concentrates on a man’s harrowing loss and his discovery of images chalked onto an overpass…that seem to move and that eventually bring him to understanding, acceptance, and peace. In “Balance,” a Force Recon vet, recently released from a VA hospital, commits outright murder but does so for the purest, most humanitarian of motives, only to have the stakes suddenly reversed. “Dance of the Blue Lady” allows a boy-man who abruptly has no place in the community to find peace and solace. A longer piece, “The Confessions of St. Zach” breaks the pattern slightly in its depiction of a United States devastated by atomic bombs. In the aftermath, Jacob Zachary, his wife, and his seventeen-year-old son initially find shelter among a small group of survivors, only to discover that safety is relative and that what is at risk is not only their lives but their humanity. In spite of the grimness and horror of the story, however, the final paragraph—indeed, the last three words—transforms and elevates it beyond its overt content.

“The Hungry Skull: A Love Story” and “Rusting Chickens” approach the power of love and loss from different directions. The first is a science-fictional story set in the same world of Cal Wild as “The Burden of Indigo” and centers on a jump-ship pilot—half human, half machine—who seems oddly entranced by a death-play at a histro-bistro, in which the actors performing in The Gunfight at the O.K.Corral literally shoot to kill. In the second, Force Recon veteran Rob McKenna becomes convinced, first that the metal chickens ornamenting the yard are moving of their own volition, and then that his wife is somehow betraying him. Both stories are tightly told and devastating in their implications for the characters—and for the readers’ conceptions of love and loss and sacrifice—yet when the end comes to each, there also comes the realization that what happens is perfectly imagined and perfectly accomplished.

I’ve not said much about the intensity with which O’Neill confronts the realities of warfare in story after story—that becomes obvious as readers explore his worlds. War destroys…even its survivors. The point is not the number of the enemy killed or the amount of territory captured or even the points of belief justified but the lasting damage warfare does to individuals and the extraordinary, often supernal, effort it takes to overcome it.

- Killing Time – Book Review - February 6, 2018

- The Cthulhu Casebooks: Sherlock Holmes and the Miskatonic Monstrosities – Book Review - January 19, 2018

- The Best Horror of the Year, Volume Nine – Book Review - December 19, 2017

- Widow’s Point – Book Review - December 14, 2017

- Sharkantula – Book Review - November 8, 2017

- Cthulhu Deep Down Under – Book Review - October 31, 2017

- When the Night Owl Screams – Book Review - October 30, 2017

- Leviathan: Ghost Rig – Book Review - September 29, 2017

- Cthulhu Blues – Book Review - September 20, 2017

- Snaked: Deep Sea Rising – Book Review - September 4, 2017