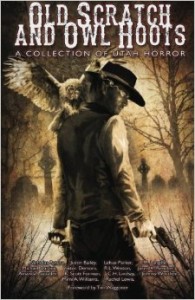

Edited by C.R. Langille and R.L. Weston

Griffin Publishers

2014

Reviewed by Michael R. Collings

The subtitle to Old Scratch and Owl Hoots, a thoroughly enjoyable anthology edited by C.R. Langille and R.L. Weston, points directly to one of the more curious facts about modern American science fiction, fantasy, and horror: an unusually high number of well-received authors hail from one relatively small area in the Intermountain West. When considering horror in particular, readers do not generally think immediately of Utah—land of wide-open deserts and snow-capped mountains, of past Olympics and future vacations, of Temples and Tabernacles. Yet the fourteen tales in this Collection of Utah Horror aptly suggest the talents, the diversity, and the power to be found there.

The “Foreword” by Tim Waggoner sets the stage for the stories by noting the appropriateness of the mythic Old West (and, implicitly, of the mythic New West) as a setting for horror: the necessary sense of isolation, physically, emotionally, and spiritually; and the frequency of legends, often associated with monsters of varying forms, that epitomize the darkness of unknown landscapes. With his final words—“Let’s ride”—he releases readers into adventures that range from the eerie to the spine-tingling, from the nightmarish to the curiously nostalgic.

Nicholas Batura’s “Washakie’s Revenge” begins in Ogden, Utah, in 1894. A few years after that, around 1900, my five-year-old grandmother made a trip to Ogden that included five days of arduous travel to go perhaps 150 miles; a wagon full of supplies; and—what surprised me most when she first told me the story—her sleeping under the wagon bed, along with her family, for protection against marauding bands of robbers. So when Batura begins by evoking a mostly-lawless Ogden, with the requisite saloon, poker game, and shoot-out, I felt at once comfortable. I had heard stories about this time and this place from an impeachable source. But as Batura’s character is taken under arrest to Salt Lake—not the City, but a small island in the lake—things take a decidedly different and uncomfortable turn, for him and for the reader. Because what he finds is more than merely another manifestation of man’s inhumanity to man. Much more.

With “Community Business,” Justin Bailey explore the definitions and limits of “communities”—what price it might take for an individual to try to separate from others and how little of value might be gained…especially when the dead seem less than content to remain dead.

Lehua Parker presents a deftly stylized riff on a classic fairy-tale in “Red.” Initially a story of a young girl kidnapped and in immediate danger of the proverbial “fate worse than death,” it skillfully reveals more and more of the situation, until it is clear that there is a girl in a red cloak, a grandmother, and a wolf. The only snag is that they do not quite correspond to what the fairy-tale leads us to expect.

“The Demon We Bring,” by C.R. Langille set in Utah in 1866, is in one sense an old-time Western and in another sense a timeless tale of love and loss, of grief and revenge, of choice and consequence.

Michael C. Darling uses “The Hollow” to create the ultimate haunted house and a hunger so desperate that it transcends time and space. The builder and his victim both discover, far too late, that “There Is No Way Out.”

Viktor Demors’ “Cold Hearted” takes place in a rough hunters’ cabin in the middle of a blizzard. Bitter, heart-felt cold can do strange things to men, as Simeon and Peter discover. When all hope but one is gone, that single choice may lead to survival…or to damnation. As with Batura’s story, this one also struck a chord. My family histories record an equally harsh winter, during which one of my forebears left wife and child to venture out to hunt. While he was gone they were reduced to existing on a broth made by boiling their horses’ harnesses; fortunately for my family, the father returned in time to save them. Demors’ characters are nowhere near that lucky.

In “Dreadful Sorry,” R.L. Weston anatomizes the indignities and inhumanities committed by railroad workers upon a camp of Chinese coolies. History merges with ghost story and—just when it seems as if cosmic justice might be served…well, these are, after all, tales of horror.

Jaren K. Rencher begins “Hunger” with Eddie Hawkins stealing through the pines, desperate to stay ahead of “Old Brigham’s Avenging Angels,” hot on his trail for a string of robberies and mmurders—or perhaps it is the Danites or, worst of all, Orren Porter Rockwell himself that he fears most. Sleepless from fear—and the haunting sense that something is nearby—he takes refuge in a lonely ranch house, where he is treated as the guest of honor at a feast. Only gradually does he realize that there is a price to be paid for the generosity.

“The Man Who Comes for You,” by Amanda Luzzader, is nicely ambiguous in its title—what does for really mean? To collect, to gather? Or to aid and support? Or both. When young Charlie McPheeny meets Jake the gunslinger and recommends his mother’s boarding house as a good place to stay, he sets in motion events that will cost lives…and save them.

K. Scott Forman’s “The Stranger Within” shows a boy struggling to understand what has happened to the father he once knew, to the man who left them to fight the Civil War and who never returned…except in body. Having relocated to a farm outside a Mormon community, Jack must stand by and helplessly watch his family self-destruct.

“Life to Life,” by C.H. Lindsay breathes new life, as it were, in to an old scenario. Young, beautiful widow mourning by her husband’s body. Virile sheriff passing by, entranced by her voice, the sense of mystery surrounding her. An offer of “…comfort.” But this time, the moment does not end as he expects.

Johnny Worthen tackles the knotty problem of polygamy in “Keep Sweet,” with a nightmarish tale of a polygamy that never was, in which men’s lust and vanity wreak pain, horror, and devastation upon their chosen innocents…until Vengeance meets the demands of Justice.

The penultimate story, Mimi A. Williams’ “The Lamb on the Tombstone,” seems at first anachronistic, talking as it does of radios and CDs and AC. A young couple, traveling south from Salt Lake City toward Zion National Park, take a side trip to a pioneer cemetery near Springdale, where the narrator becomes intrigued by a time-worn stone surmounted by a carved lamb, its only inscription being two dates in May, 1865. Driving further south, David shares a bit of family history, including the fact that a relative was buried in the old graveyard…and that the family member had been cursed. Camping near the Virgin River, Amanda hears a baby’s distant cry…and it draws closer and closer.

With “Earthbound,” by Rachel Lewis, the collection comes to a triumphant close, with a first-person, present-tense narrative of a musician—Mssr. Duval—and his secretary, who penetrate the wilderness searching for music in a place “where the melody should never be discovered.” As Duval moves further into the unforgiving desert, plagued by hunger and thirst and his private obsession, the narrator—the Land itself—watches as ghosts are drawn from the soil by his music. It is a fitting conclusion…lyrical, symbolic, evocative, and entirely appropriate to the landscape that has given birth to the tales.

My family has deep roots in the Utah wilderness of the long-ago that extend to today. Reading Old Scratch and Owl Hoots, concentrating as it does on horror, on darkness, on death and distress and despair, I nonetheless felt the authenticity of many of the stories. In many ways, they bring together images, ideas, characters, and conflicts that are unique to that particular landscape…and that at the same time speak to universals of human experience.

Well done—strongly recommended.

- Killing Time – Book Review - February 6, 2018

- The Cthulhu Casebooks: Sherlock Holmes and the Miskatonic Monstrosities – Book Review - January 19, 2018

- The Best Horror of the Year, Volume Nine – Book Review - December 19, 2017

- Widow’s Point – Book Review - December 14, 2017

- Sharkantula – Book Review - November 8, 2017

- Cthulhu Deep Down Under – Book Review - October 31, 2017

- When the Night Owl Screams – Book Review - October 30, 2017

- Leviathan: Ghost Rig – Book Review - September 29, 2017

- Cthulhu Blues – Book Review - September 20, 2017

- Snaked: Deep Sea Rising – Book Review - September 4, 2017