Lee Murray

Cohesion Press

April 13, 2016

Reviewed by Michael R. Collings

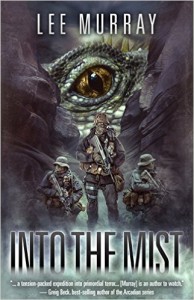

Reading Lee Murray’s Into the Mist is like watching Jurassic Park again for the first time. From Dean Samed’s highly evocative cover, you know that there will eventually be a dinosaur—or something very like it—followed by oohs and ahhhs and then running and screaming…and dying. You just don’t know when or how or who.

Then there is the added bonus of another filmic reference, this time to the Lord of the Rings films by Peter Jackson, with their exploration of the exotic mountain wilderness of what is in the real world New Zealand. Gorgeous…and deadly.

But what is perhaps most important about Into the Mist is that it manages to capture many of the stock images and motifs of creature-features—on the screen or in books—and combines those elements that trigger almost automatic responses of awe and horror and fear and adrenaline-fueled excitement into a single, coherent, highly imaginative and ultimately impressive narrative. The characters, for example, at first seem fairly standard: the self-involved scientist who thinks it is a good idea to capture a creature that has already killed twenty or so people; the plucky female willing to undergo a personal hell in order to save the day; the stolid military guy, muscles on muscles, who nevertheless sacrifices all for his companions and those under his protection; the canny native whose knowledge of myth and legend become far more important than at first seems possible. But Murray gives each sufficient individuation that they become more than merely ciphers to be moved around as the plot demands. They become intriguing personalities that either grow or diminish through their abrupt exposure to the unknown.

The story begins in New Zealand’s Te Urewera National Park as two hikers first discover what they assume to be fossil moa eggs in a recent landslide…and soon thereafter discover how mistaken they are. Several months—and a dozen more deaths—later, James Arnold of the New Zealand Defence Force Army base in Waiouru orders Sergeant Taine McKenna and his men to accompany a small group of scientists and civilians into the Te Urewera wilderness, ostensibly to protect them from possible attack by Tūhoe separatists. In fact, they are to search for an earlier group of soldiers and find out what is going on. But even Arnold and McKenna know nothing about clandestine plans to force the government to open the wilderness to gold mining. Or the hidden marijuana farm. Or the self-appointed guardian trying to keep outsiders away. Wheels within wheels within wheels.

Lest this sound as if Murray has simply thrown everything into the mix, there is one more ingredient that almost miraculously holds the story together: Rawiri Temera, an eighty-three-year-old makakite, a seer, who has been dreaming of the coming of the Taniwha, a monster from Maori legend. His insights guide the story through the collision of science and myth, of the possible and the impossible, ultimately providing the key to the sole means of destroying not only the Taniwha but the evil within it.

Murray makes effective use of her sources. There are frequent references to horror films at key moments, accentuating her narrative with readers’ memories of other monsters. She develops the native mythologies well, weaving them through the story rather than simply overlaying them and asserting the supernatural. In the New Zealand of Into the Mist, there are monsters; there are lands that should remain untouched; there are secrets that should not be investigated; and there are constant reminders that, as one character says, “Stories exist for a reason.”

- Killing Time – Book Review - February 6, 2018

- The Cthulhu Casebooks: Sherlock Holmes and the Miskatonic Monstrosities – Book Review - January 19, 2018

- The Best Horror of the Year, Volume Nine – Book Review - December 19, 2017

- Widow’s Point – Book Review - December 14, 2017

- Sharkantula – Book Review - November 8, 2017

- Cthulhu Deep Down Under – Book Review - October 31, 2017

- When the Night Owl Screams – Book Review - October 30, 2017

- Leviathan: Ghost Rig – Book Review - September 29, 2017

- Cthulhu Blues – Book Review - September 20, 2017

- Snaked: Deep Sea Rising – Book Review - September 4, 2017