Weston Ochse

Cohesion Press

May 25, 2015

Reviewed by Michael R. Collings

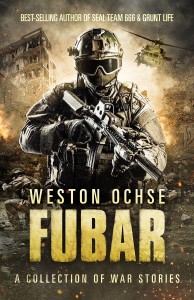

Weston Ochse’s newest collection of short stories, novellas, and non-fiction is titled FUBAR—military slang for “Fouled Up Beyond All Recognition”—although many intimately familiar with the term could easily provide an alternate for the first word. Regardless which version one choses, however, FUBAR has a single meaning: if anything can conceivably go wrong, it will.

Since several of the tales have appeared in Cohesion Press’s ongoing SNAFU series (“Situation Normal, All Fouled Up,” with the same option for the final phrase), the title FUBAR seems appropriate, resonating to a similar theme. What I found more interesting, however, was the subtitle: “A Collection of War Stories.” The phrase is both apt—in that all of the selections deal with war in some way—and inapt, almost misleading. These are not simply run-of-the-mill, gung-ho, take-that-hill-boys tales of military exploits and, presumably, military heroism. No, they go far deeper and are far more important than that.

To begin with, as Ochse does, not all of the selections are stories in the traditional sense, although even in those that are not he constantly weaves a web of story around reality. The “Introduction”; the first essay, “Welcome to the War Zone”; a Soldier of Fortune article, “We All Wanted to be Heroes When We Were Young”; “My Thoughts on PTSD”; “The Importance of Building Your Own Shadow”; “Every War Has a Signature Sound”; and “Finishing School” all address fact-based essentials relating to warfare and being a warrior, as do the useful authorial postscripts Ochse provides for each piece. These nonfictional pieces provide a mortar of sorts for the intervening stories, building on them and amplifying them until the entire book embodies what it is like to be involved in war. As Ochse says at the end of the introduction:

This is my journey.

Now it is yours.

This is not to suggest that the underlying nonfictional structure is more important than the individual stories. It is not. Like a jeweler’s foils, however, it perfectly highlights and intensifies the stories themselves.

For readers of the SNAFU series, the collection begins on a comfortable, familiar note, although “When I Knew Baseball” is anything but comfortable in content. The storyteller’s first-person, present-tense, colloquial tone suggests a typical war story (if there is indeed any such thing)…that is, until he says “We knew it was coming. The damned thooloo hadn’t fed on any Japs in more than two weeks….” And abruptly the Guadalcanal of 1942 morphs into a story of self-knowledge, of memory and identity, of conscious sacrifice in the face of that which is pure darkness and evil and incomprehensibility and paradoxically necessary…and of Lovecraftian nightmares.

From that moment on, readers should advance cautiously, constantly alert, observing everything the story has to offer, prepared for any shifts—or purposeful misdirections—the enemy (if I may momentarily and metaphorically tag the author as such) has placed in the way. In some of the war stories, not a shot is fired, although that does not in any way dampen the sense of devastation and loss in the horrifically ironic “Family Man,” the tragic (in the classical sense) “The Road to Painted Rock,” or the disturbing snapshot of basic training that is “Doctor Doom’s Guide to the Universe and Special Rules for the Burial of Christian Insects,” with its juxtaposition of matter-of-fact statements with cadence songs, of the expansive with the trivial, and its pervading theme that “all is violence.”

In others, including “The Last Kobyashi Maru,” “Rhythm,” and “Righteous,” shots are not only fired but they threaten to end worlds and desolate individuals.

Yet others begin as real-world recreations, only to move into worlds of fantasy—which can be frightening and terrible—and horror, as in “Hiroshima Falling,” with its images of bomb-seared flesh wrapping itself around survivors and forcing them to share the memories of the dead; or “Tarzan Doesn’t Live Here Anymore,” in which the aliens and their mindless destruction seem minor compared to the damage humans can do to each other; or the Lovecraftian incursion in “Fugue on the Sea of Cortez,” with its explorations or courage and selfhood; or the intense grittiness of the Iraqi war in “On Tranquility Tides I Ride,” which transforms into something much more when Nathan begins receiving cell-phone calls from his dead brother and—after following him into the depths of pain, suffering, and misery—converts his greatest loss into a lyrical Cosmic Voyage.

Every story engages. Every essay or article intensifies. And by the end, one comes to the inescapable conclusion that, although the pieces were written at various times over the past eighteen years; appear here out of chronological order; and form no perceptible sequences of time, place, or landscape, they do in fact create a coherent whole. And at the core of that meta-story, lies a warrior constantly defining and re-defining himself: Weston Ochse.

- Killing Time – Book Review - February 6, 2018

- The Cthulhu Casebooks: Sherlock Holmes and the Miskatonic Monstrosities – Book Review - January 19, 2018

- The Best Horror of the Year, Volume Nine – Book Review - December 19, 2017

- Widow’s Point – Book Review - December 14, 2017

- Sharkantula – Book Review - November 8, 2017

- Cthulhu Deep Down Under – Book Review - October 31, 2017

- When the Night Owl Screams – Book Review - October 30, 2017

- Leviathan: Ghost Rig – Book Review - September 29, 2017

- Cthulhu Blues – Book Review - September 20, 2017

- Snaked: Deep Sea Rising – Book Review - September 4, 2017