Eternal Darkness

Tom Deady

2017

Bloodshot Books

Reviewed by Michael R. Collings

Tom Deady recently received the Bram Stoker Award® for his first novel, Haven. Reading his second novel, Eternal Darkness, will give readers a good indication of why. His is a strong, powerful hand, creating a dark, believable world, peopled with complex and interesting characters, some of them necessary types but none flatly imitative stereotypes. His landscapes are appropriately dark as well, from the lonely streets of Bristol, Massachusetts at night to the highly uninviting interiors of the Old Brewster House, the local “Bad Place,” where murders have taken place and worse is still to come.

Within the first few pages of Eternal Darkness, Deady suggests that though his story takes place in Massachusetts in 1979, the events are not far distanced in either time or place from other signal locations in New England, especially such small towns as Castle Rock or its sister city Derry in the ghoul-haunted forests of Maine. His characters almost immediately suggest King’s strongest adolescents, from the four boys from Castle Rock who suddenly and inexorably must face life as it truly is in “The Body” to the collection of outcasts and misfits who discover terror and truth, life and death in the tortuous sewers beneath Derry.

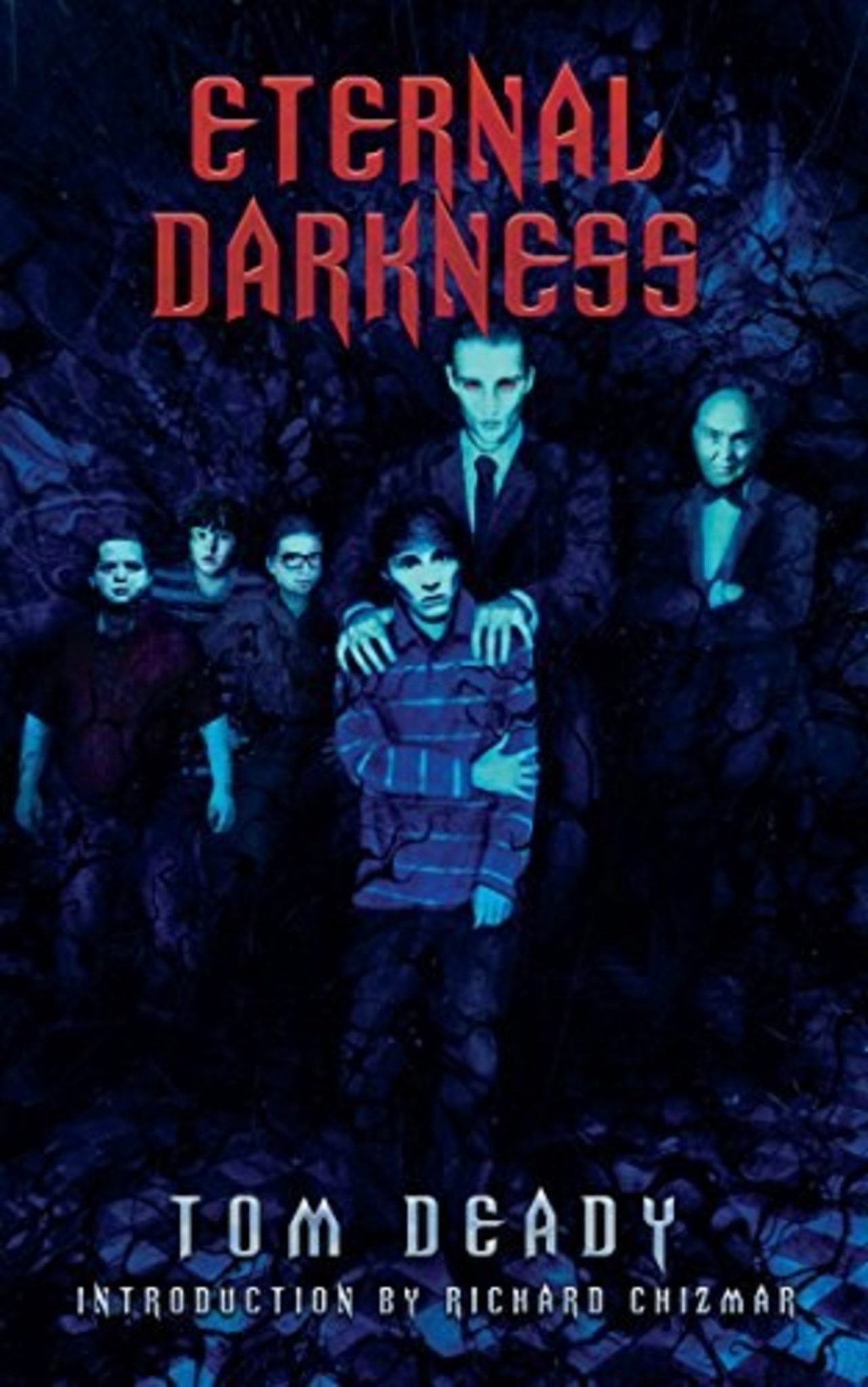

But the story most connected thematically to Deady’s world is ‘Salem’s Lot. Unlike that novel, the cover of which gave its first readers little clue as to the specific horrors about to be confronted, Ben Baldwin’s moody design, with its overwhelming darkness and angular, eerie figures, leaves little doubt as to what lies within.

Vampires.

And those who must challenge them.

Fourteen-year-old Ben Harris, his friends Richie and Jack (even the names tingle spookily with memories of IT), and later his six-year-old sister Eve, become friends with the new boy in town, Greg Lupescu, lately moved into the Old Brewster House. Greg’s father, Alexandru, is oddly missing through the first chapters, at least as far as the boys know. But Greg’s butler-cum-handyman, Karl, is almost too much present…and when he is nearby Ben and his sister both experience devastatingly realistic and horrific visions of lines of human crosses.

Much of the atmosphere in Eternal Darkness echoes familiarly (after all, how many variants on the archetypal small-town Bad Place can there be?), but Deady’s story is far more than simply ‘Salem’s Lot retold or a yet-another-vampire-novel expedition into tradition and lore. True, he involves—and often invokes—such time-honored tropes as the crucifix, the mirror that shows no reflection, the aversion to daylight, but in doing so he systematically re-thinks the vampire, re-designs the parameters in much the same way that Whitley Strieber did in The Hunger (1981). He brings to it a revitalizing power, such as appears in Robert M. McCammon’ The Thirst (1981—a good year for vampires), that energizes the traditions and brings them into the reader’s own world in unusual and highly imaginative ways.

My only frustration (and even that is too strong a word) with Eternal Darkness is that as the reader nears the conclusion, it seems a complete story in its own right, with a gruesomely fitting climax that ties most of the threads together. I say “most” because one of the most crucial characters, alluded to toward the end but neither fully introduced nor fully developed within it, remains outside the scope of this novel…and hence, there is the implicit promise in the final pages of a sequel.

There is nothing wrong with that, of course. And the abruptness of the revelation is perhaps superior to an overt subtitle, no doubt printed in red letters and dripping bloody ink, announcing that this is “Book One in the Evil, Awful Vampires Series.” But it is abrupt and a bit disruptive.

Still, it leaves open the possibility of another book as strong, as well-handled, as engaging as Eternal Darkness, in which the secrets Greg must face and the losses Ben, Richie, Jack, and Eve incur must be repaid. I look forward to that story.

- Killing Time – Book Review - February 6, 2018

- The Cthulhu Casebooks: Sherlock Holmes and the Miskatonic Monstrosities – Book Review - January 19, 2018

- The Best Horror of the Year, Volume Nine – Book Review - December 19, 2017

- Widow’s Point – Book Review - December 14, 2017

- Sharkantula – Book Review - November 8, 2017

- Cthulhu Deep Down Under – Book Review - October 31, 2017

- When the Night Owl Screams – Book Review - October 30, 2017

- Leviathan: Ghost Rig – Book Review - September 29, 2017

- Cthulhu Blues – Book Review - September 20, 2017

- Snaked: Deep Sea Rising – Book Review - September 4, 2017