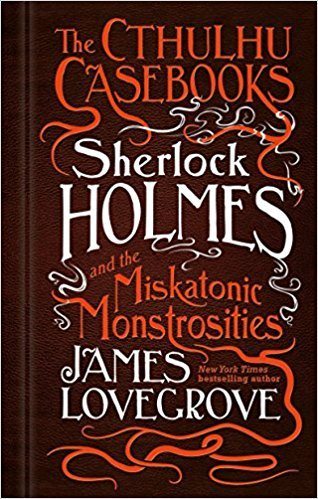

The Cthulhu Casebooks: Sherlock Holmes and the Miskatonic Monstrosities

James Lovegrove

Titan Books

November 2017

Reviewed by David Goudsward

Sherlock Holmes and the Miskatonic Monstrosities is Book Two in a proposed trilogy starting 15 years after the first volume. Holmes and Watson are near the breaking point from their endless war against the Mythos. They are called to Bedlam Lunatic Asylum, where they find an inmate speaking in R’lyehian, the language of the Old Ones (which Holmes is fluent in). They discover he was a student at Miskatonic University, but they cannot explain his amnesia, his missing hand, or his scarred face.

Lovegrove overlays the insanity of the Cthulhu mythos on the rational Victorian mindset, but with uneven success. He is well-established as a Sherlock Holmes writer but he seems to struggle with the Cthulhu elements, slipping into the amateur trope of name dropping Cthulhian gods. As one example, there is no reason Dunwich would be on anyone’s watchlist in 1895 London. The horror starts in 1923, and Wilbur Whateley and his brother were not born until 1913.

The book consists of short chapters that end on a cliffhanger as if the story were a movie serial. Two hundred pages of the 459-page book are the journal of a doomed steamship expedition up the Miskatonic River. In addition to stopping the main storyline dead, it feels like the main purpose is to pad the word count. The alleged cause of the expedition’s failure was an attack by Wampanoag Indians, which is not as it seems. The use of Wampanoags would be appropriate if the river flowed through Providence, not Arkham. Wampanoag territory didn’t extend into “North Central Massachusetts” where Lovecraft places Dunwich, which he notes is in the Miskatonic River Valley. That would be Nipmuc or Abenaki territory, but an Indian attack in New England that late borders on absurd regardless of which tribe. It may be nitpicking, but it demonstrates at best a superficial familiarity with the primary source material – H. P. Lovecraft himself.

There are some marvelous parts – Lovegrove is at his best when he’s working with Watson’s literary career. The good doctor, it seems, has been sanitizing Holmes’s adventures for publication, turning battles against supernatural horrors into the common criminal cases of the original books. The Hound of the Baskervilles, for instance, was really a hellhound. Unlike the name-dropping mythos references, these are clever references to the A. Conan Doyle body of work. And Holmes’s encounter at Badlam with the supercilious ass of a doctor named S. Joshi is a hilariously accurate cameo.

It’s a decent, if not spectacular, addition to the increasingly crowded Sherlock/Cthulhu crossover market, but Lovegrove’s strength is not Lovecraft. His steampunk Sherlock Holmes work is much stronger.

- ‘eyes I dare not meet in dreams’ by Sunny Moraine - October 7, 2019

- Bill Hodges Returns in the Trailer for MR. MERCEDES Season 3 - August 21, 2019

- Release Details and Cover Art for Tom Savini’s Official Biography SAVINI - August 7, 2019

- IDW Publishing Announces Comic Book Series Based on Stephen King and Owen King’s SLEEPING BEAUTIES - July 29, 2019

- From Raw Dog Screaming Press: Preorder STEEL SHADOWS by J.L. Gribble - July 26, 2019

- Available Now from Crystal Lake Publishing: A new Poetry Collection by Stoker Award-Winners Linda D. Addison and Alessandro Manzetti - July 24, 2019

- From Raw Dog Screaming Press: Preorder On the Night Border by James Chambers - July 22, 2019

- From SDCC 2019: Watch the Trailer for New CREEPSHOW Series - July 19, 2019

- Evil Moves in Next Door in the Teaser Trailer & Poster for THE WRETCHED - July 18, 2019

- Hex Studios Unleashes A Legion of Demons In ‘For We Are Many’ - July 18, 2019