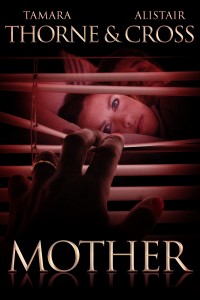

Tamara Thorne and Alistair Cross

Glass Apple Press

April 9, 2016

Reviewed by Michael Aronovitz

If I went insane, would I know it? Are there degrees? Is my reality so warped and fabricated that it plays out before me as if comprised of moving portraits projected by some grand simulator, or does it lay over the rises and contours like some glorious masking device, a mosaic in lovely pastels, smooth lines and elegant patterning draped across the rough divots and sharp edges of some bleak and less forgiving existence? I have often joked with my students about this, teaching the given college Introduction to Literature class focusing on stories dealing with various sorts of madness, like The Yellow Wallpaper, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, and even The Lottery, then going off on a tangent, claiming “You know, guys…I often wonder if I really am crazy, and worse, whether or not I would know it if I was. I mean, how can I be sure that I am not actually standing right here and now in some padded room in a mental asylum, and you’re a bunch of doctors observing me on the monitor, elbowing each other in the ribs, saying, “Hey, there he goes doing the professor thing again, look at him go!”

Laughter. It’s all good.

I suppose the reason why I raise this issue, is that I just finished reading Mother by Tamara Thorne and Alistair Cross, and while this, their third novel, haunts, sickens, engages, mystifies, and terrifies its audience, there is a wonderful structural device they toy with that cleverly brings the reader into the writing process itself, and in doing so, introduces theme and symbol in an undeniably personal manner. And this is extraordinary, being that the idea they illustrate is so very technical on literary grounds to begin with, launching the project into the arena with M. Night Shyamalan having us reevaluate character presence at the end of The Sixth Sense and Quentin Tarantino playing with flashbacks and timelines in Pulp Fiction. The interesting distinction here is that concurrent with these mechanical acrobatics, Shmalayan merely gave us a ghost story and Tarantino provided no more than outrageous misfortunes (though both scripts were exceptionally well written and clever). Not to be in any way comparative, Thorne and Cross merge their own brand of stylistic virtuosity (and rebellion) with the elusive idea of madness, symbolized no less, in an inventive manner that pleasantly guides us through a maze leading to a critical stance, opening our ability to synthesize behind-the-scenes structuring devices, philosophical psychology, and emblem, all of these configured in the shifting paradigm defining insanity, reality, and perception.

A bit heady?

No problem. Before the lit-geeky stuff, let’s talk nuts and bolts. The story is a good one, giving us an immediate sense of tension, as if A Streetcar Named Desire, suddenly smashed head on into Mommie Dearest. Our lead character Claire Holbrook is pregnant. Her sweet husband Jason lost his job being a pilot because of the occasional epileptic seizure, and money is so tight they decide to travel to the town of Snapdragon and move in with Claire’s mother, Priscilla Martin (Prissy). Claire is wary of this since she had a rather nondescript unhappy childhood, most of it currently repressed. Jason is optimistic he can win over this “tough matriarch,” and they move into “Mother’s” picture perfect home, in the picture perfect suburbs, in the picture perfect cul-de-sac, so “All American” with yard sales, bake-offs, church functions, and events planned by the Ladies Auxiliary, we almost get a feeling of temporal disorientation, like the place is stuck in the 1960s. Like Mother.

Of course this is the easy metaphor, the tease. Underneath the facade of beauty lies the beast, masterpiece draped over monster, or more story-specific in this case, the garden cloaks the serpent. The town is called Snapdragon, and the streets are all named for flowers. Considering the many coordinated activities Prissy imposes on her neighbors, the most important is the annual “Morning Glory Circle Snapdragon Contest,” that which Prissy Martin always wins, and it is easy to recall our first literature classes through which we learned that when a garden is introduced into the setting it is an obvious allusion to our most popular, traditional, and familiar symbol, Old Testament, Eve tempting Adam with more than an apple and all that. Of course Thorne and Cross play this out front like a kid waving an essay with a big red “A+” on it, saying, “Lookie here, Pa, I done good!” but it is actually just a baiting device. Not to play too much of a spoiler, it must be said here, that the Eden symbol is capped off later in the piece in a dream sequence, when Prissy open her legs and a snake slithers out of her pussy, coming for a priest no less, and so what appeared to be cliché has a shocking underside. Device mirrors symbol. And this literary phenomenon is just the warm-up!

In reference to plot and surface conflict, the authors are aware that the readers can guess what is coming from the introductory pages. Claire and Jason will move in with Claire’s mother. At first it will be fine, yet soon we will discover the depth of Prissy Martin’s evil. Nuts and bolts. Good stuff. To make matters more interesting, we soon find out that the woman sleeps with old dead stuffed dogs, wears a necklace made of a lock of hair from her dead son Timothy, and keeps her invalid husband locked up in a small room. And this is the behavior she shows openly! As the story progresses we find out more and more about the past atrocities this woman inflicted upon her children, through old journals found under floorboards and repressed memories brought to the surface by our heroine Claire Holbrook, all in a manner that would make Sigmund Freud beam with pleasure. Of course there is some authorial tap-dancing in the center of the piece, where Jason’s naiveté makes him question whether it is actually Claire who is imposing blame on the mother unfairly, seeing things and losing her hold on herself, and toward the end we are brought to what I believe is more important as pre-climax than the big, violent ending, when the neighbors all gather in the cul-de-sac to admit to each other all the secrets Prissy was blackmailing them with. Again, not to play spoiler, this closes out the aforementioned theme of temporal dissociation, acknowledging that times really have changed and in this day and age of social media, exposure, and lack of privacy, even the worst secrets are only a part of the white noise for a hot minute, and then we move on. It’s a brand new age of frightening (and liberating) transparency.

But there’s more.

Of course there is.

Tamara Thorne and Alistair Cross don’t only write provocative fiction. They are unabashed innovators, mad scientists if you will, performing freakish experiments on contexture and mainstream techniques, openly challenging convention, satirizing trends, and for this I applaud them. Personally, I was quite tired of hearing a few years ago the latest whispers around the industry that insisted first person voice was a sloppy second to third person limited, flashbacks were a no-no, and linear plotting was the only acceptable structural conduit. In response, I wrote Phantom Effect, a serial killer / supernatural thriller that utilized first person in pre-chapters and third person limited for the balance, a funhouse of flashbacks, and timelines so multi-directional the book itself became a haunted road-map of sorts. I sold it to Nightshade Books, released February, 2016. I hear it is doing well; so much for convention.

Thorne and Cross have been living here all along. To begin, Tamara Thorne has an impressive backlist including novels such as Haunted, Candle Bay, and The Sorority Series, many written in an occasionally omniscient voice, something editors typically frown upon. Tamara smiles right back, knowing full well she possesses the experience and mastery of the craft to offer up narrational complexities and make them as relatable as old folk talk and family adages. Her sense of sport is no more evident in reference to past work however, than in Eternity (2001), where we are introduced to a cavalcade of townspeople presenting themselves as famous deceased archetypes, like Jim Morrison and Ambrose Bierce, each claiming the “other” is off his or her rocker, winking and smiling no less, then proposing that the supernatural exists right here in the very fabric of our day to day grind. And in the swirl of double irony and parodies of parodies, we wonder whether she as author believes just a tad in the wild proposals of her clever protagonists. It’s “I know that you know that I know that you know” gone wild, isn’t it? The Chicken and the Egg on steroids.

Tamara’s new writing partner Alistair Cross formulates his own brand of “the rebellious cliché” in a subtle strategic technique that would mask more embedded symbolic terrain in his debut solo novel, The Crimson Corset, seen most clearly in his choices for setting. For the reader at first might chuckle at the idea that the protagonist lives in a spacious and most tastefully peaceful hacienda surrounded by lush forest green and sparkling fountains, when the antagonist resides in the tunnels under a biker bar with a huge garish windmill in front of the door, the overall effect more the miniature golf course in a Swiftian nightmare than the digs of a believable villain. That is, until we determine that Cross was never bothering with “good and evil” to begin with. He drew us in with boardwalk flash and sidewalk chalk in order to make the more profound and relevant statement that we are living in a dangerous world of “real versus replica,” making the characters our own caricatures, looking in the mirror and wondering what on earth is staring back.

Thorne and Cross’s first full length novel The Cliffhouse Haunting had its own special version of the bait and switch, in that we initially got so tied up in the raucous (and rather hyperbolic) behavior of the protagonists and background cast, that we were hit extra hard finally realizing the only order in this universe belonged to the ghosts and their maniac assassins. Clearly, these two authors are not only masters of decoy and deception, but they do it with a sardonic sense of humor, daring the reader to address what would seem to be cracks in the foundation only to expose caverns and dark chambers far more embedded and personal than advertised.

In the case of Mother, there is a third stylistic element to add to the clever shock-and-awe framing technique used to allude to and expose the Garden of Eden symbol, and the colorful (yet patient) illustration over the course of the text that would unveil the more timely thematic epiphany proving that privacy has become an antiquated ideal.

It is a gaming element.

Surprise, surprise.

As mentioned earlier, Thorne and Cross establish an open sort of omniscient narration in this book, not only switching point of view when the sections change, but within scene units, between characters directly engaged in dialogue with each other. This in itself is nothing so “new” or “revolutionary,” though many editors fear this kind of ping-pong effect for the sake of clarity. In the creative writing class I teach at The University of the Arts in Philadelphia, I always recommend a singular viewpoint to start, as many new writers struggle with getting their “he’s” clarified without overusing speaker attributions within a tight third person limited viewpoint, let alone being inside everyone’s head all at once. But Thorne and Cross have been around the block a few times, and I would claim here that during the read, not only was I consistently clear as to who was thinking what, but the narration was as spot-on as “the one” I had always held up on a pedestal as the greatest engineer of the omniscient voice: Louisa May Alcott.

The instance that literally made me catch my breath in my throat, blink hard, and gulp twice however, occurred when we went inside Prissy Martin’s head. In the middle of the book. During her plotting phase.

Pure and unadulterated blasphemy.

Flagrant foul.

Once you go into a character’s viewpoint, especially that of a conniving antagonist, the jig is up and the mind is fair game, opened like the sea, all secrets revealed. The author cannot “conveniently” hide things at that point. It’s like cheating, and even readers the least critical, just turning the pages for a surface run of action and eye candy, will inevitably come out of the read for a moment, look off blankly, and say, “Huh?”

I finished the text, admittedly satisfied overall and even a bit envious, but I just couldn’t get this one thing out of my mind, this one chink in the armor. It didn’t make sense, especially since there is a large portion of the piece leading up to its climax through which Jason believes what Prissy is telling him, consequently doubting his wife’s sanity. Since Jason remains our most reliable narrator throughout the read we are led down that path with him, and considering the fact that Prissy is lying to him, we simply cannot go into her point of view and be left ignorant of her plans and intentions. It would be like reading a murder mystery, having the author place us inside the head of the killer, and then having him oh-so-conveniently “not be thinking about the murders at that particular time.”

There had to be a catch.

As “lofty” as this might seem in the current context, the idea I was wrestling with was no more advanced than “showing and not telling,” or actors banking on emotional recall, or singers using their diaphragms. There had to be a catch.

Catch.

Hasps.

Locks.

Of course.

Wrapped up in such a complicated (and unique) thematic and metaphorical design, and involved with such a large cast of characters so intricately drawn, I had missed the most significant symbol of the lot. Prissy Martin is a hoarder, locking away her past in dark rooms so over-stuffed that even she cannot possibly connect with all the parts and parcels. The rooms she uses “for show” are perfect replicas of sane living, magazine worthy, showroom quality, everything polished and set in place in flawless line and dimension.

Prissy’s house is a metaphor for her mind, and she has learned to compartmentalize madness, to hoard and therefore hide psychotic behavior and evil, even from herself. Of course we go into her point of view and remain partially blind. She shares our affliction. On purpose. She leads us on a grand tour that only reveals the guest-friendly sunporch, the House Beautiful living room, and the Ozzie and Harriet Hollywood kitchen. The darkness is locked away in the forbidden rooms upstairs, only accessible when convenient.

Not for her authors.

For her. And that might be the scariest part of this story.

While privacy is a thing of the past out there in the cul-de-sac and the brave new world of social media, Prissy Martin introduces us to a new kind of terror. For she uses internal privacy as a weapon, a cloaking device that lets her hoard evil, lock it away, and rationalize its existence. Saved for a rainy day. Or a sunny one, when she can unlock one of those doors and unleash whatever beast she has buried there, divorced from her conscience and lethal in its purity.

- Mother – Book Review - May 6, 2016

- Horror Metal Review: Forever Still - January 4, 2016

- Horror Metal Review: The Bloody Jug Band - December 22, 2015

- Horror Metal Review: Ravenscroft - December 9, 2015