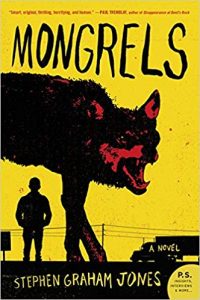

Stephen Graham Jones

Wm. Morrow/Harper Collins, 2016

Review by Bret McCormick

What’s it like living in a werewolf family? What happens when a werewolf gets old? If werewolves exist, why aren’t we certain of it? How have werewolves adapted to modern conveniences like automobiles? What happens to a werewolf’s clothes during the transformation? What if they’re wearing panty hose? Why do werewolves burn their garbage regularly? Does a werewolf ever fail to convert back to being human?

In Mongrels, Stephen Graham Jones answers all these questions and many, many more.

On January 28, 2017, my friend E.R. Bills attended a book signing in Port Neches, Texas, and got me a signed copy of this book. For reasons both legit and frivolous, I never started reading it until two days ago. Thanks for the book, ER! Thanks for the autograph, Stephen!

The narrator’s a kid, and he speaks with the unvarnished clarity that comes natural to children. What was that show with Art Linkletter? Kids Say the Darnedest Things! When a kid lives with werewolves, his sayings are darned to the nth degree.

In America it’s considered a disadvantage to be poor. Not so much if you’re an American werewolf. Those sudden transformations triggered by anger simply wouldn’t fly in the boardroom or on the golf course. On the poor side of town, mostly no one notices. And if someone dies? Oh, well, it’s just way things happen on that side of the tracks, right?

Listening to this mongrel lay it all out, I realize growing up in a werewolf family isn’t much different than how most of my friends had it in Poly on the eastside of Fort Worth. Lots of hotdogs to eat, lots of moving around for jobs and to stay a step ahead of trouble. Hotdogs? Yeah, werewolves eat a lot of them when they’re not wolfed out. Go figure.

Coming of age tales – they’ve been a staple of novels and movies for decades. This one has much in common with all the others: insecurity on the part of the narrator; strange characters the protagonist must sort through to decide which he will emulate; that first kiss; what’s important and what’s not and the ultimate realization that the thing that matters most is family – even the family members who bug the shit out of you. “We’re all outcasts” is one way of looking at the big picture and that’s especially true if you’re a werewolf.

Jones is clearly a fan of the werewolf subgenre of horror. I noticed nods to virtually every werewolf film I’d ever seen. It wasn’t just me filling in the gaps with my imagination. In an acknowledgements sections at the end of the book, he ticks each of the connections I’d noticed off his checklist. I felt there was a solid connection to Kathryn Bigelow’s groundbreaking vampire flick from 1987, Near Dark, as well. The character Darren in Jones’s novel seems a lot like Bill Paxton’s Severen in the movie: supernatural ne’er-do-wells having a few kicks and surviving the best they know how on the fringes of human society.

Turns out there are many permutations in the interface between human and werewolves. The werefolk themselves aren’t quite sure what’s truth and what’s legend. They live in the moment. Not the sort of individuals who keep records or write historical accounts. Because of the narrator’s unique set of circumstances, it’s not certain he’ll ever be a werewolf himself, even though that’s what he wants more than anything. There’s more than a little shame involved in being a lame-ass human liability in a family of creatures who wouldn’t hesitate to eat you if you weren’t kin. So it goes.

Does the kid make it? I’ll never tell. It’s a hell of a story either way.

- Book Review: ARTERIAL BLOOM - April 6, 2020

- Book Review: DEAD END - April 1, 2020

- Book Review: MONGRELS - March 21, 2020

- Book Review: WHISKEY AND OTHER UNUSUAL GHOSTS - March 17, 2020

- SUMMER OF LOVECRAFT: Book Review - March 9, 2020

- Advance Review: SWITCHBOARD - February 17, 2020

- WHISPERS IN THE EAR OF A DREAMING APE: Book Review - February 8, 2020

- Book Review: PENDULUM GRIM - January 31, 2020