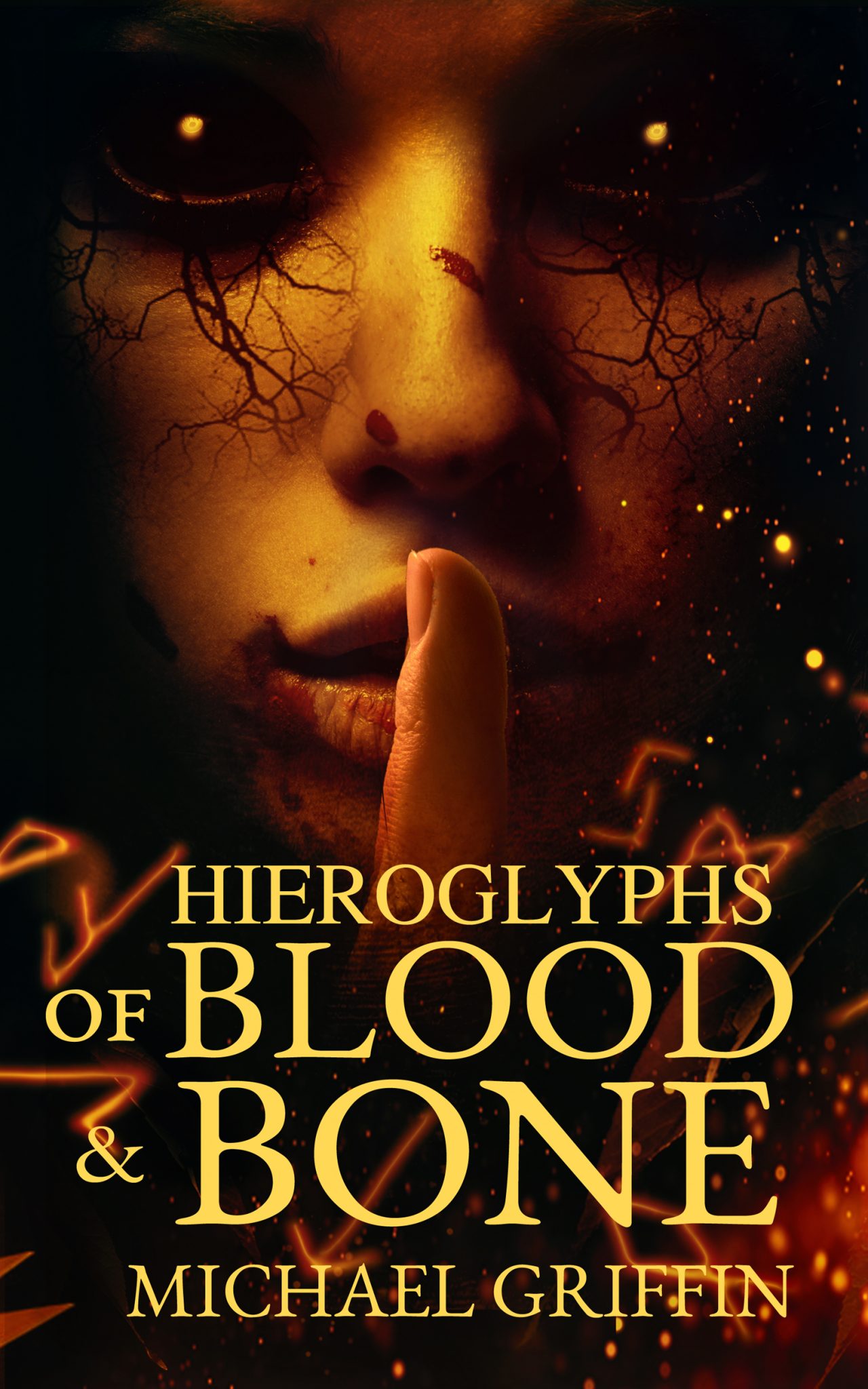

Hieroglyphs of Blood and Bone

Michael Griffin

Trepidatio Publishing

February 2016

Reviewed by Michael R. Collings

Although the word is often applied to stories of horror and terror, few weird tales can legitimately claim to be phantasmagorical—composed of real or imaginary images resembling those experienced in dreams.

Michael Griffin’s Hieroglyphs of Blood and Bone is among the few.

The book begins solidly in consensus-world reality, with the first-person, present-tense narrative of Guy’s divorced life following a twenty-year marriage. The pages are replete with details of his life sharing a houseboat with a younger co-worker, including extended conversations that characterize the clash of two generations; with his obsession over his ex-wife and his conflicting sense of attraction and repulsion; with his discovery of a mysterious woman living in a cabin along the Kalama River. All very straight-forward and uncomplicated.

Until somewhere along the way—and the dividing line is as difficult for readers to discern as it is for Guy—everything shifts, becomes surreal, kaleidoscopic, impossible…phantasmagorical. People, places, events become as ephemeral as time itself, which simultaneously seems to expand and contract in the most unexpected ways. Seems. And perhaps does. Perhaps.

What results is a novel in which everything becomes increasingly emblematic, standing for something else far more complex, which in turns reveals itself to be illusory…or possibly delusory. Each detail, from the façade of a wealthy man’s wilderness retreat, to the image of steel-head holding steady against constant down-river currents, to books containing arcane, untranslatable symbols—Hieroglyphs of Bone and Blood—each element of storytelling becomes a means of entering, exploring and at times almost understanding a human psyche disintegrating as abruptly as Guy’s marriage had disintegrated.

Guy is fascinating both as himself and as representative of humanity—in many ways, he is ‘just another Guy’—and the events that enfold him may be taken on several levels as analogues to human life: loss, betrayal, hope, fear, uncertainty, insecurity. His mystery woman, Lily, is as transient as the lilies of the field; and the only Constant in his life is his boss, known only by that name. As the story progresses, Griffin plays with language, with signs and symbols that may or may not have meaning; Guy’s life builds “upon hints, toward full comprehension. Language is a code” (168).

One particularly interesting point: toward the conclusion of Hieroglyphs of Bone and Blood, Guy systematically divests himself of the accumulations of his former self, the old Guy, including several books: Thomas Wolfe’s Look Homeward, Angel; Charles Baudelaire’s volume of symbolist and modernist verses, Les Fleurs du Mal; and perhaps most centrally for understanding the novel, Ernest Hemingway’s collection of short stories, In Our Time. As Guy places a candle on the book and sets it adrift on the Columbia River, he in essence recapitulates Nick Adams’ desperate attempts to understand a world gone mad by immersing himself in the minutiae of a fishing trip in “Big Two-Hearted River”…and the image of fish struggling to maintain equilibrium and position in a constantly flowing river flashes into mind, confirming the iconographic, emblematic nature of Griffin’s book.

Hieroglyphs of Bone and Blood is ambitious in conception and scope. Its language is Hemingwayesque in its seemingly disarming simplicity while at the same time the perfect vehicle for telling Guy’s story. As with the patient fisherman, the patient reader will find much to appreciate and to enjoy.

- Killing Time – Book Review - February 6, 2018

- The Cthulhu Casebooks: Sherlock Holmes and the Miskatonic Monstrosities – Book Review - January 19, 2018

- The Best Horror of the Year, Volume Nine – Book Review - December 19, 2017

- Widow’s Point – Book Review - December 14, 2017

- Sharkantula – Book Review - November 8, 2017

- Cthulhu Deep Down Under – Book Review - October 31, 2017

- When the Night Owl Screams – Book Review - October 30, 2017

- Leviathan: Ghost Rig – Book Review - September 29, 2017

- Cthulhu Blues – Book Review - September 20, 2017

- Snaked: Deep Sea Rising – Book Review - September 4, 2017